Courage under fire

Published 5:10 pm Thursday, December 22, 2022

- Smoke billows from the USS Curtiss (left) after being struck by a Japanese dive bomber at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Contributed Photo

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Part 1 of a series

By Linda Dudik

Early on the morning of December 7, 1941, the USS Curtiss was one of 27 auxiliary ships on the north side of Ford Island at Pearl Harbor. The Curtiss was at the entrance to Middle Loch in the North Channel, moored in berth Xray 22.

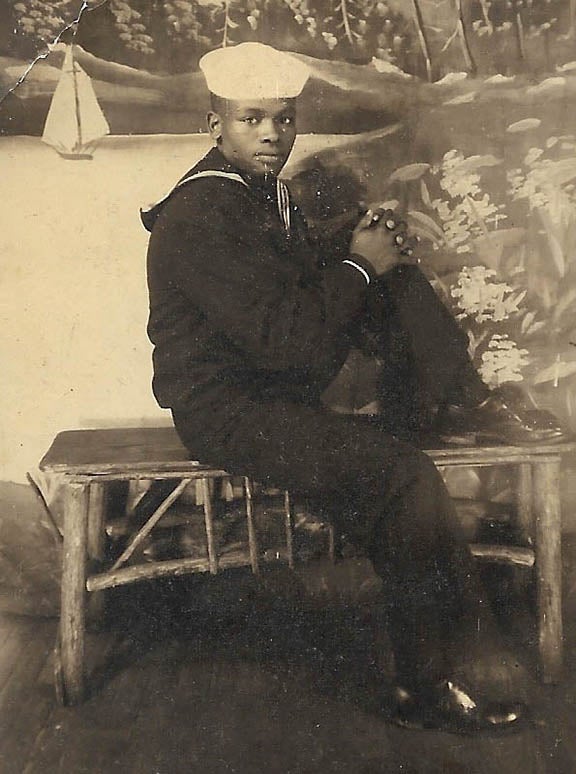

Gates County native William Jeremiah Powell was on board the Curtiss, which served then as a seaplane tender. He was not in the group of 55 enlisted sailors who were on shore leave, most of whom had probably left the ship the day before.

According to the Curtiss’ after-action report, written nine days later, at 7:50 a.m. those on deck saw Japanese “torpedo and bombing planes” attack the Naval Air Station on Ford’s Island as well as ships in the harbor. As the after-action report continued, “Bomb hits observed on [the] patrol plane hangar at the Naval Air Station and at Hickam Field.” (Hickham was an Army air base.)

Battleship Row was located on the southern side of Ford Island. The seven battleships moored there were the primary targets of the enemy planes. Still, action was heavy on the northern side of Ford Island, too. Around 8:00 a.m., the crew of the Curtiss watched as torpedoes hit ships moored nearby; one capsized. The guns on another, the seaplane tender Tangier, shot the tail off one dive-bomber and claimed it had helped to bring down two more. One of those dive-bombers crashed into the Curtiss’ starboard crane.

Gates County native William Jeremiah Powell was among the 20 sailors killed onboard the USS Curtiss when the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor 81 years ago. Contributed Photo

As all of this was happening, William would have gone to his battle station. We do not know exactly where that was. The ship’s command assigned every sailor to a General Quarters, or battle station, position and task. On other ships, including auxiliary ships like the Curtiss, messmen such as William could be assigned to a General Quarters position topside. They might be part of gun crews that loaded the guns. They were not assigned to be part of the crew, however, that fired the guns. The Curtiss’ after-action report detailed specific times when the crew acted in defense of Pearl Harbor. The report also specified what damage the enemy inflicted upon the Curtiss, both in terms of material damage and in respect to loss of life.

At 8:03 a.m., the Curtiss began firing its .50-caliber machine guns. Two minutes later, the ship’s 5-inch battery and other guns were “firing continuously.” Japanese bombers attacked the Curtiss at 8:25 a.m. but with no discernable damage.

The attack turned deadly for the tender at 9:05 a.m. when the ship’s guns hit one of three enemy planes coming out of a dive over Ford Island. With his aircraft severely damaged, the pilot either purposely targeted the Curtiss, or he lost control of his plane. It crashed into the starboard side of the tender, causing a fire. Before sailors could get the flames under control, a bombing attack on the Curtiss began by other enemy aircraft. One bomb exploded in the hanger, which resulted in more fires. Another bomb hit the starboard side of the boat deck; it passed through the carpentry shop and radio repair shop after which it entered the hanger and exploded on the main deck. As described by the after-action report, “the bomb destroyed bulkheads, decks, equipment, and fixtures within a radius of 30 feet from the point of detonation.” The bomb also resulted in several fires. In the conclusion of the after-action report, “All fatalities occurred as a result of this detonation or from fires resulting from this hit.”

At 8:35 a.m., crewmen saw a periscope from a Japanese midget submarine in the waters; it was about 700 yards away from the ship. The Curtiss opened fire and hit the sub’s conning tower at least twice. Another U.S. ship targeted the sub with depth charges; the Curtiss’ after-action report added that “air bubbles and slick” then appeared on the water’s surface.

During the Japanese attack, the Curtiss downed one Japanese plane, about 1,000 yards off the port bow, with machine gun fire. The crew watched it break into pieces in the air. The after-action report claimed that guns from the Curtiss hit at least three enemy planes. Crewmen extinguished the fires on the tender within 30 minutes. Twenty sailors died and 58 were injured in the December 7th attack. Of the 20, two could not be identified. Of those injured, 33 were transferred off the ship to the naval hospital while the injuries of 25 others were treated on the ship. One crewmember was missing-in-action.

William Jeremiah Powell was one of the crewmen who had died in the attack. The Curtiss’ muster roll for December 28th contains the following phrases next to William’s name: “Killed in action December 7, 1941, on board. Body tran. [transferred] to U.S.N.H. [U.S. Naval Hospital] Pearl Harbor. T.H. [Territory of Hawaii] NOT MISCONDUCT.”

In a larger picture, William was one of 79 Black sailors in the Navy’s messman’s branch who died on December 7th. Of the 2,403 servicemen killed that morning, 2,008 were members of the Navy. Messmen thus constituted 3.9% of all the Navy crewmen who lost their lives. The percentage reflects how few Black sailors there were on the ships in Pearl Harbor. For every 100 enlisted sailors there, nonwhites totaled not more than 3 or 4 of that number. How many were on each ship depended on the size of the vessel. On December 7th, the battleship USS Arizona had a crew of over 1,000 men; 24 were Blacks, 6 Guamanians, and 5 were Filipinos. By the end of the war four years later, at least 1,176 messmen had lost their lives in combat.

Many of those sailors died when the Japanese sunk their ship. William’s death was different than those. He may very well have died while directly engaging the enemy.

Years after the war, William’s family received an account of that moment from a sailor on Ford Island. The story originated with Navy aviation ordnanceman Joe Morgan, a Pearl Harbor Survivor. In his words, “When the gun operator on the crane deck [of the Curtiss] spotted the burning plane headed for them, they ran…a black messman grabbed the deserted gun, making eye contact with the pilot and began to fire directly at the plane, bringing it down. The plane plunged into the deck, starting a fire. Of course, he and the pilot died.”

A crewmember of the Curtiss must have shared these details with Morgan. According to Morgan, the “black messman” who fired the machine gun was the only Black sailor killed on the Curtiss in the attack. If this account is true, it testifies to William’s courage under fire. His nephew, James C. Powell, shared his reaction to Morgan’s story.

“I felt a sense of pride.” James said. “He didn’t die in vain, not drowned and helpless. He died fighting the enemy…”

James also has an explanation for the puzzling phrase that appears on the Curtiss’ December 28th muster roll, in capital letters, “NOT MISCONDUCT.” William’s nephew believes it is a reference to the fact that his uncle fired the gun, which Black messmen were not to do.

Recall, too, the phrase from the after-action report on the Curtiss’ casualties–“All fatalities occurred as a result of this detonation or from fires resulting from this hit.” Again, if William fired the machine gun and directly caused his own death, he died because of his heroism, not as the result of indirect actions beyond his control. Even so, one of William’s brothers always said, “He should not have jumped on that gun.”

Burials in Hawaii of the Pearl Harbor defenders took place within days of the attack. Initially, their caskets came to rest in three nearby cemeteries–Halawa Cemetery, Nuuano Cemetery, and the Schofield Barracks Cemetery. William’s remains were initially buried at Halawa as “body #180.” There it remained for at least six years.

Next: William Jeremiah Powell comes home.